When the BJP won a landslide mandate of over 300 seats in Uttar Pradesh during the 2017 assembly elections, it was considered as a culmination of the saffron party’s long-term campaign to bring Hindutva and caste politics together. The BJP’s masterstroke in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections was this, and the mandate in the 2019 general elections was just the cherry on top. With the outcome of the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP humiliated the grand coalition of the Samajwadi Party and the Bahujan Samaj Party once again. However, in the run-up to the 2022 assembly elections, it appears that the BJP’s efforts to reconcile caste divisions under a bigger Hindutva umbrella are in jeopardy.

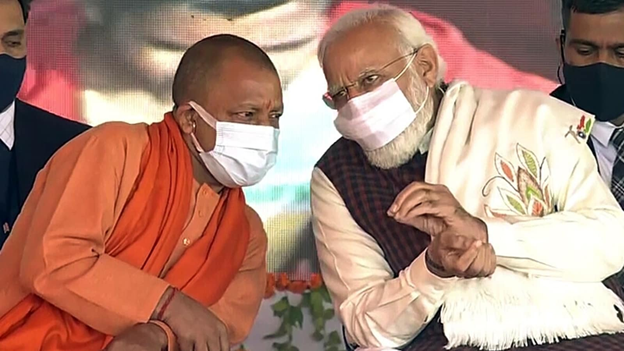

So far, 11 OBC parliamentarians have defected from the BJP, including three ministers. Their beef is with Yogi Adityanath, the chief minister, rather than the party’s senior echelon. Five years of ‘Brand Yogi’ appears to have stirred the caste cauldron in UP, with whispers of discontent among OBCs and Brahmins.

In Uttar Pradesh, the BJP has fought with caste issues for years. Hindutva and the concept of cultural nationalism were frequently thwarted by politics arising from backwards caste and Dalit concerns. In the mid-1980s, the BJP attempted to strike a compromise between its Hindutva-based philosophy and caste dynamics. With the RSS-BJP-led Ram Janmabhoomi agitation gaining traction, UP was also becoming a birthplace of Hindutva politics. When the BJP surged to power with an overwhelming majority in 1991, the ideology of Hindutva, which envisioned the unification of disparate castes under a bigger banner of religious consciousness, experienced initial success. Hindutva has temporarily triumphed over caste dynamics.

The Mandal Commission report had only recently been implemented, and the Dalit agitation led by the BSP was still gaining traction. The RSS was alarmed by the threats posed by a new wave of caste awareness. The appointment of Kalyan Singh, a famous OBC Lodhi figure, as UP CM was considered as part of a long-term plan to smooth up caste divisions. Even while competing upper-caste BJP politicians vied for the top post, the RSS backed Kalyan, describing him as a “natural leader.”

However, when the Babri Masjid was demolished in December 1992, the Ayodhya movement’s enthusiasm subsided. It was also a time of comeback for the Dalit-based BSP and increasing Mandal politics. The BJP was at a fork in the road once more.

The BJP tried to balance Hindutva and caste issues for over two decades after that. While it did gain power in the meantime, the wider politics was dominated by the BSP and SP. However, the commencement of the Narendra Modi era, which began ahead of the 2014 elections, marked a significant shift for the BJP.

The BJP’s use of the Hindutva card might be due to a possible rupture in the caste system. With Ayodhya already in the mix, Kashi and Mathura are also up for argument. Adityanath, too, attempted to give the election a clear “majority vs minority” spin by declaring that the election is “80% versus 20%.”

The reality remains, however, that the BJP’s 60 percent alliance of upper castes, non-Yadav OBCs, and non-Jatav Dalits is what made the party tick in 2017. The Mandal worked for the BJP in the last election as part of its ‘Kamandal’ agenda, which is a blend of Hindutva and Mandal politics. Backward castes are set to play a critical role once more in a state where OBCs are anticipated to make up approximately half of the population. Even while the BJP still has a strong battery of OBC and Dalit leaders, the most visible of whom is Prime Minister Modi, it remains to be seen whether ‘Brand Yogi’ can work its magic once more.